In light of some the major moments happening in the world of internet search (SearchGPT, Antitrust Lawsuits), I'm going to be writing a series of short posts on the past, present, and future of search. The utopian case for the internet has, to my mind, always been the navigation of all accumulated human knowledge, and so the fight over search represents to me a larger fight over the future of the internet.

This second post is about examining all of the different search typologies we are engaged in, and looking ahead to how they might evolve for the future.

The Marketplace

This is the form of search that's most popularly available to us as modern Internet users: platform marketplaces. Whether Google, or Bing, or Yahoo, or whatever, the basic premise is that platforms make money by bringing searchers and answers, buyers and sellers, together in mutually beneficial exchange. In order to function, they rely on a set of "convenient and widely believed legal and cultural fictions: That they are fair, neutral, and, maybe most importantly of all, that neither the platforms as corporations nor any of the specific people who work for them are liable or accountable for the kinds of things you find on them."

In practice, things are muddier than this. The constant tension between content farms trying to game a platform's search algorithm to appear more important has led to a flood of spam, while the tension between a marketplace as a service (providing access to high-quality information) and a marketplace as a business (selling ads) leads to potentially problematic conflicts of interests. Wouldn't a marketplace be tempted to send people to the links that are most profitable? And then wouldn't that degrade its product?

The final problem with the marketplace model is that it's inefficient and a bit of a slog. It has been called the "global internet thrift shop" and that's a fitting analogy. You need to comb through a lot of garbage to piece together an answer to any sort of open-ended, ambiguous query.

The problems notwithstanding, in their purer form (think of federated wikis), they represent something like a utopian vision of what the internet can be. Crowd-sourced, democratic, and pluralistic knowledge bases that provide a lot of different ways to think about a particular topic. Wouldn’t it be nice if all of the internet was like Wikipedia?

But sometimes we don’t want to do the work of exploring. We want something to just tell us the answer.

The LLM Answer Machine

On July 25th, OpenAI announced the prototype launch of SearchGPT, their newest digital product. SearchGPT is a formalization of one of the most sought-after use cases for Generative AI, search (very creative naming by the OpenAI team). It's largely a continuation and improvement of what people have been using ChatGPT for, which is also as a kind of search engine.

There is one very clear reason why people have bet on the search capacities of an LLM: it reduces the cognitive load inherent in the traditional platform marketplace model. You, the searcher, no longer needs to go to the "global internet thrift shop" and piece together the answer you need. You are served it on a platter. The PR announcement of SearchGPT says as much, "Getting answers on the web can take a lot of effort, often requiring multiple attempts to get relevant results. We believe that by enhancing the conversational capabilities of our models with real-time information from the web, finding what you’re looking for can be faster and easier."

SearchGPT remains largely a black box -- it's only available to a very small set of users, so it's useful to think a bit about why the incorporation of LLMs as a search technology is more checkered than the AI-boosters might think, without completely giving up on its usefulness to the search process.

Crucial to the "LLM serving answers on a platter" worldview is that the part of search "where readers piece together answers and context out of the documents of others" is seen as merely a transitional technology. What we have really been waiting for is the Star Trek Computer which composes its infallible answers out of nowhere. Nevermind that the Star Trek Computer represents a wildly outdated idea of information technology, one in the idea that computers could be used for text processing was considered ridiculous.

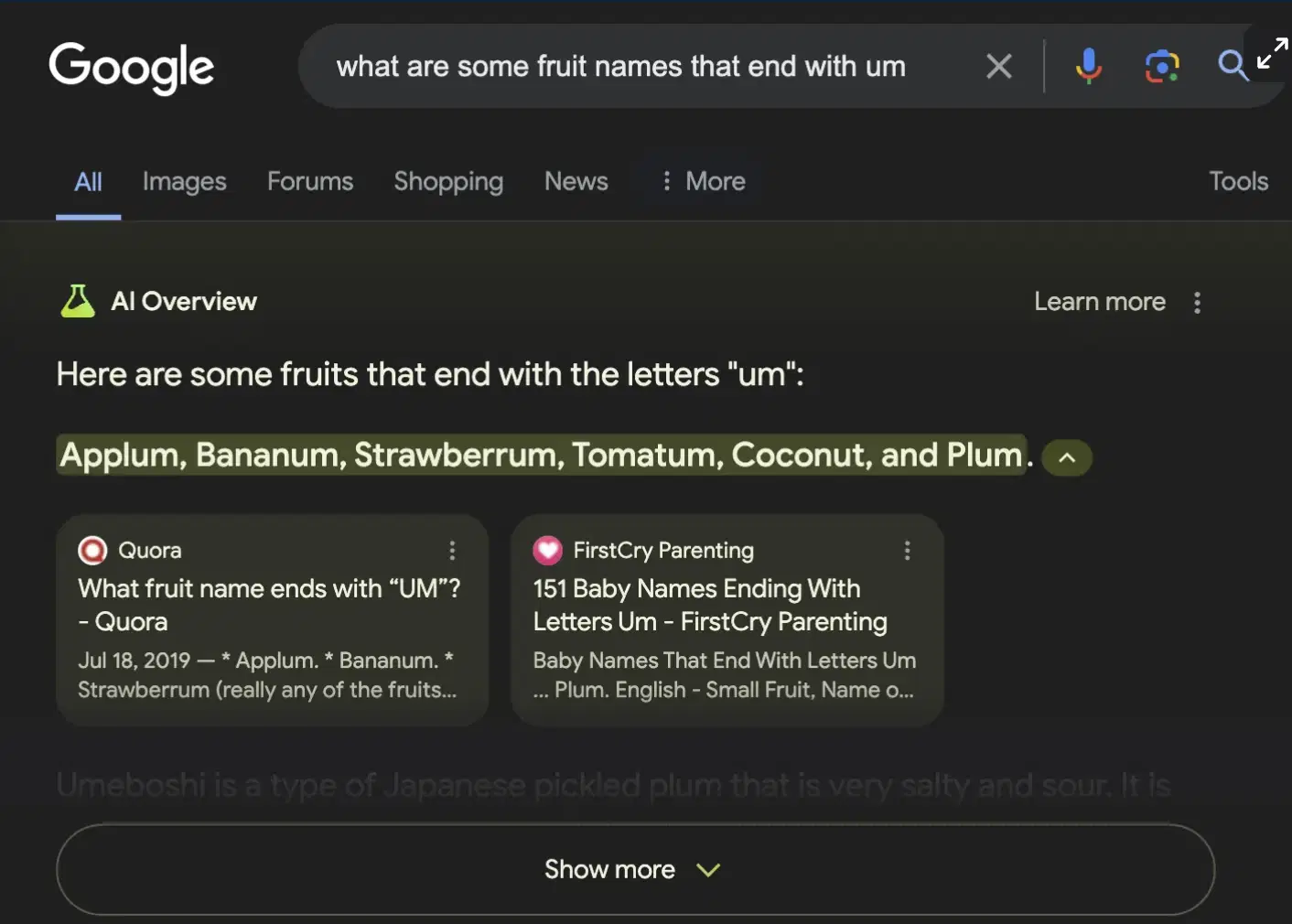

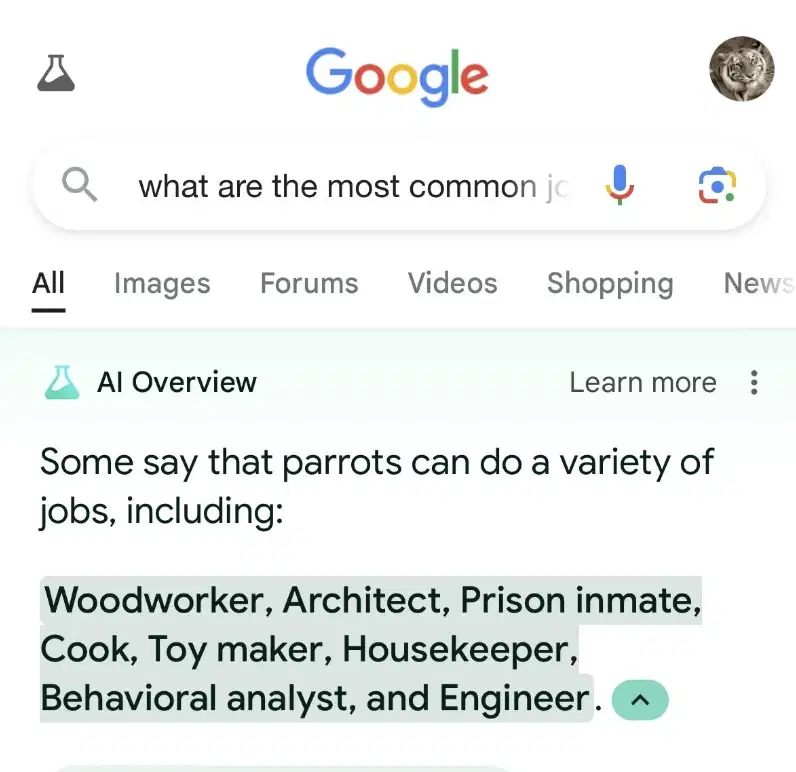

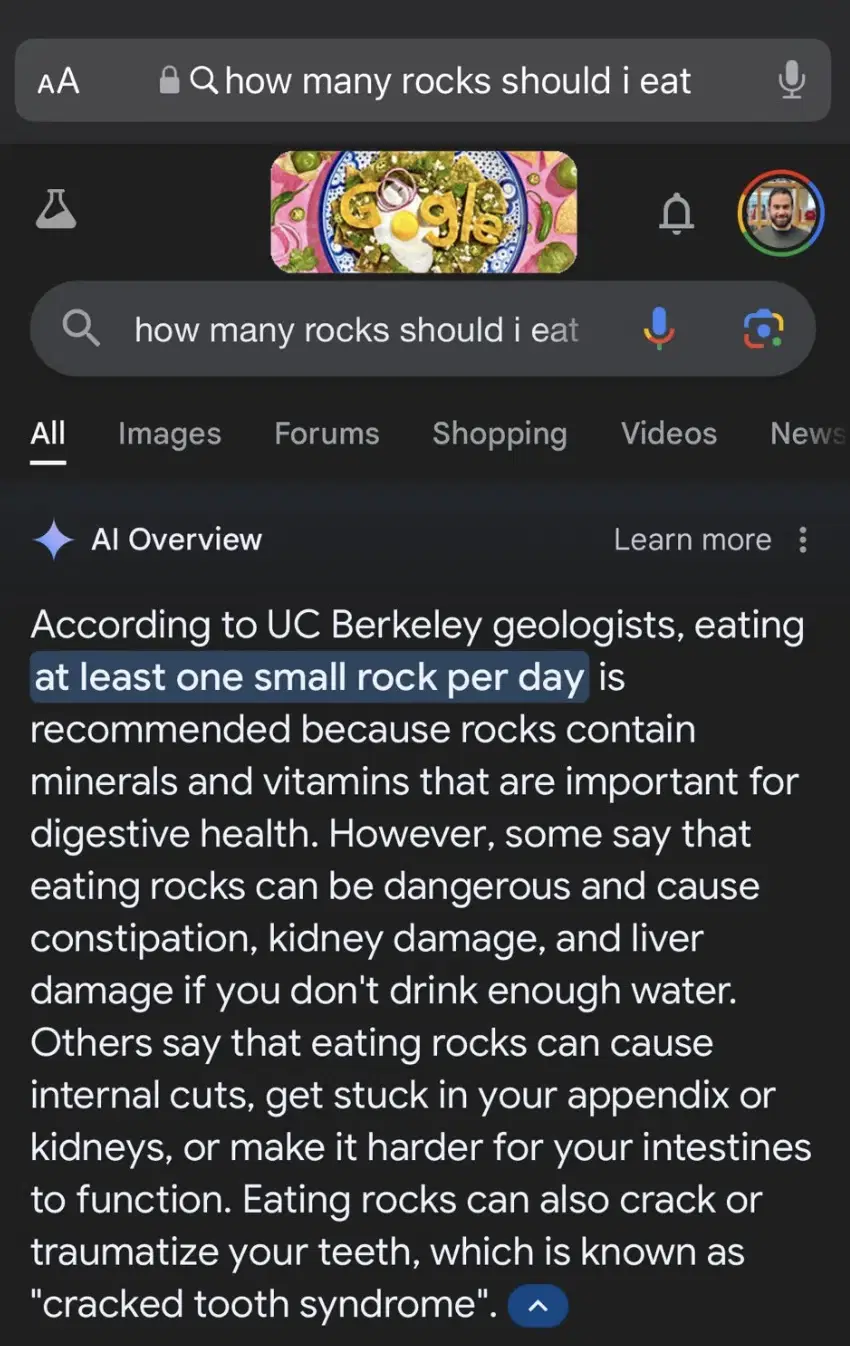

And yet, there's been an uneasy mix of this kind of thinking even amongst the platform marketplaces. Take Google's "AI Overview" feature, for example, which uses their LLM to synthesize and summarize search results into a paragraph or two. The results have been... mixed.

The manner of these kinds of search failures, its "context collapse", are interesting, and hint at a lack of coherence in using LLMs as a search function. In a post by Mike Caulfield he explains the strength of the Google product:

"Since intent can’t always be accurately read, a good search result for an ambiguous query will often be a bit of a buffet, pulling a mix of search results from different topical domains. When I say, for example, ‘why do people like pancakes but hate waffles’ I’m going to get two sorts of results. First, I’ll get a long string of conversations where the internet debates the virtues of pancakes vs. waffles. Second, I’ll get links and discussion about a famous Twitter post about the hopelessness of conversation on Twitter.

For an ambiguous query, this is a good result set. If you see a bit of each in the first 10 blue links you can choose your own adventure here. It’s hard for Google to know what matches your intent, but it’s trivially easy for you to spot things that match your intent. In fact, the wider apart the nature of the items, the easier it is to spot the context that applies to you. So a good result set will have a majority of results for what you’re probably asking and a couple results for things you might be asking, and you get to choose your path."

When you try and combine all of these intentionally diverse results into a summarized answer, you are going to end up with something that looks weird. For instance a person putting “how many rocks to eat a day” into Google is almost certainly looking for the famous Onion article that talks about that — it makes sense that that would be the top result, followed by a number of results saying, by the way, don’t eat rocks. A good result set has both. But when these get synthesized into a single answer, the result is bizarre.

Google, of course, has responses to these instances of bad search results (that they are faked and/or uncommon queries), and that, by and large, user sentiment has been positive. But even so, the core offer of Google is that it creates a marketplace between people looking for a thing and people providing that thing. LLMs are not marketplaces. They do not bring you into contact with any other parties for mutually beneficial exchange. You are talking to the computer whose inner-workings and decision-making processes are intentionally opaque.

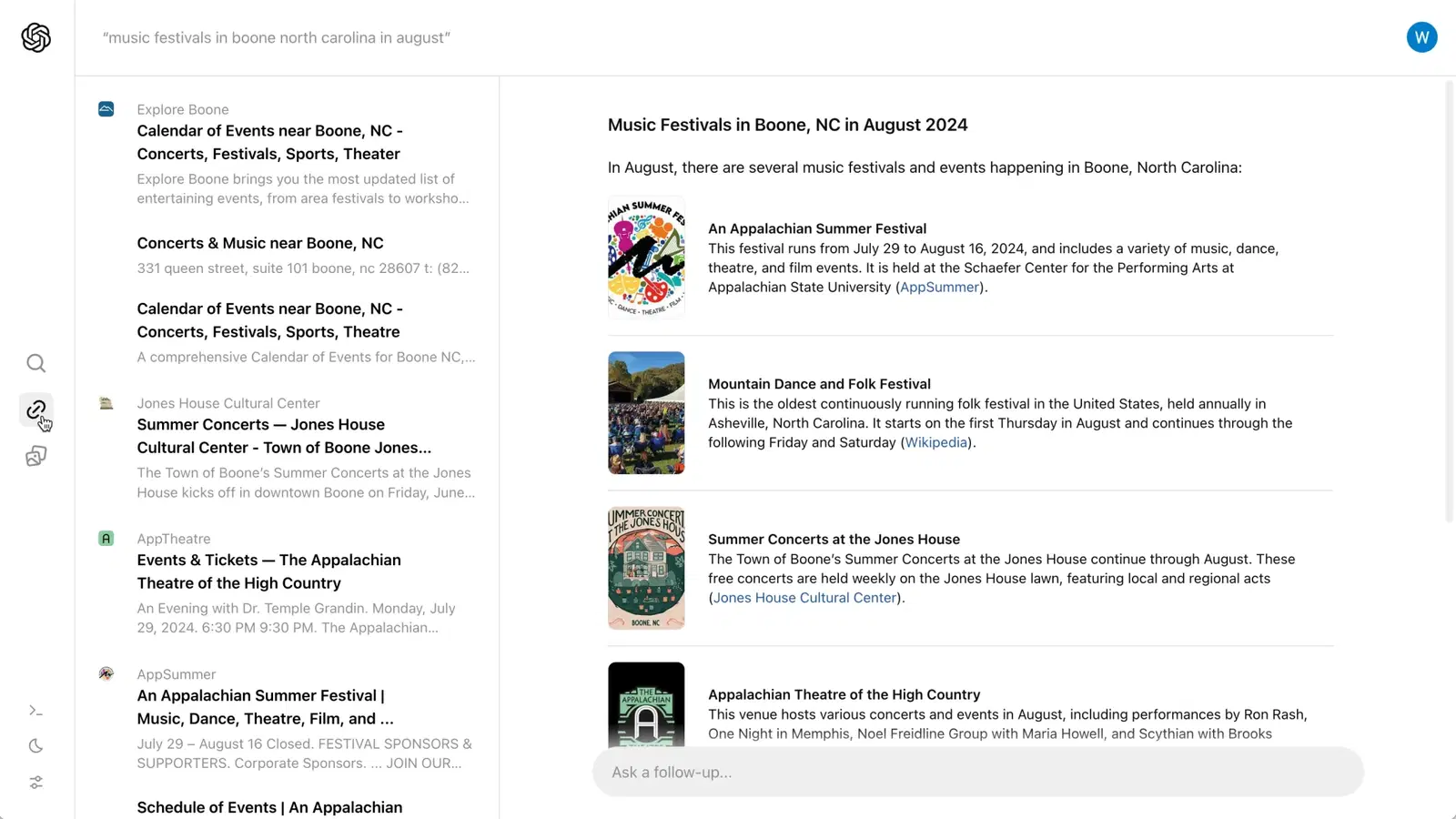

Will SearchGPT fix this? One of the major departures from ChatGPT, at least in the prototype screens they've provided access to, is that SearchGPT cites their sources, prominently displaying them and linking to the source.

We know where the LLM is pulling its answers from and why. This is good! This gets rid of the "answer from nowhere" Star Trek computer problem.

But it introduces another issue. Part of why companies and other sites allow a platform marketplace to scrape their data for free is that the platforms drive traffic to the sites. In a conversational LLM-model world, this isn't happening. The models are being trained on data they are scraping from published content on the web, but they aren't sending users back to where they got the content from. There's nothing in it for the content publishers.

This has led publishers to legal recourse. Condé Nast has sent a cease-and-desist letter to Perplexity AI, accusing the company of scraping its data without permission. More recently, a trio of authors have sued Anthropic, the company behind the Claude, for training its chatbot on a massive trove of pirated books (a dataset called Books3).

But with SearchGPT, OpenAI has indicated that they will both provide the links to the original source of the data, and pay publishers of the content for access. OpenAI has already shelled out millions to ink deals with companies like NewsCorp, The Atlantic, Le Monde, Shutterstock, and more.

This leads to a more speculative question about exclusivity. Google has paid $60M to Reddit for access to the sites content. In return, results from Reddit won't show up in any other search tool. The days, then, of search engines engaged in a mutually beneficial marketplace between publishers and the sites they appear on is looking more and more like it'll be a remnant of the pre-AI world. Not so much because what AI-powered chatbots offers are better (in certain cases, they are markedly worse), but because their interaction paradigm -- the question then summarized answer -- has significantly altered the landscape of how publishers are discovered online, and therefore what concessions they're willing to give to AI companies / search engines. If you're no longer receiving directed traffic, then you need cash to compensate for the lack of discovery. This has broken the tacit agreement of the web. Now, accessing a website will cost money for data scraping robots.

Predictive Markets and Social Navigation

There are all sorts of social cues we pick up on in order to map out our understanding of the world around us. We walk past a food truck with a line around the block and think "wow, they must serve really good food." Or, we see an empty club on a Saturday night and think "wow, there must be something wrong with that place." We trust collective social knowledge to steer us towards the right decisions. Don't go to the club that's empty when it should be full. Such is our frustration at the dim-witted characters in horror movies: don't go into the basement where you know the killer is hiding, we want to scream at them! Everyone knows that nothing good happens in a dark basement in a horror movie.

To a degree, what a website Yelp or TripAdvisor is trying to do is codify that social knowledge into reviews. Instead of an empty line outside of a restaurant, we see that it has 2.4 stars on Yelp and that the food is under-seasoned. But what about questions that don't so easily lend themselves to a quantified amalgamation of consumer sentiment? A line outside might tell us if a restaurant is any good, but what if we want to know something more abstract, like the state of the economy? Where is the codified social knowledge for that question?

Well: you might go to an online betting market. Here, you can place bets yourself on the likelihood of Fed Rate increases, the inflation rate, the amount of jobs added in August, and even on the chance of a bank failure before September (odds are currently at 2%). Much of the actual content of a site like Polymarket is geared towards crypto betting and sports gambling, but a predictive market presents an interesting use case for search -- not as an archive of past events, but as a way to see the collective social opinion on the likelihood of state of events coming to pass. It's crowd-sourced information, and one assumes a degree of veracity of the information because people are putting money on the line. If there was an obviously ridiculous scenario, all you'd need to do was bet against it and you'd get richer. Money is a good incentive to try and be right.

I have it on better authority than mine that speculation -- the process of engaging and embracing volatility in the hope of financial gain -- has become one of the defining approaches to contemporary life. In UCL Sociologist Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou's 2022 book, Speculative Communities, he lays out a wide-ranging case for how our attitude towards the future has fundamentally changed post-2008 with the global market crash signaling a "momentous historical shift." If, before 2008, life had been predictable with the promissory logic of economic growth and debts that got paid, the spectacular failure of the financial system that undergirded this logic left us with a "collective experience of uncertainty" instantiated by things like "labor precariousness, rent dependency, indebtedness, emotional insecurity, and political instability."

What's important in this account is that, in the transition from certainty to uncertainty, is just how fundamentally we have taken up the role as speculators in our everyday lives. Take Uber, for example. The once-simple act of hailing a cab has turned into a complicated guessing game of whether or not the price of a ride will go up or down.

Komporozos-Athanasiou makes a larger sociological argument about the types of communities formed through speculation -- people buying stocks based on Reddit threads, populism spread as a way to "shake up a system," commodified digital infrastructures like TikTok or Tinder that connect people based on whims and unpredictability of the Algorithm. These are all ways in which people gather around and embrace uncertainty and volatility, projecting a sort of "imagined community" based on a common narrative (ie, "Evil Wall Street short sellers are screwing us over," "the political system is fundamentally broken").

In the world of predictive market and search, then, the key is always that it's always reliant upon a sort of self-forming community that gathers around a topic. To participate in prediction is fundamentally a social activity; making a wager on who will win the presidential election based on accumulated social signals is a more complex yet similar example of checking the line outside of a club to see if it's any good. We assume the collective wisdom of the crowd is right.

My own wager is that prediction markets will become popular as a search only insofar as they provide a useful barometer for events outside of the crypto, college football, and Telegram world. What I like about them as an idea -- the collective social knowledge of people forming a sort of democratic consensus on the likelihood of an event -- is also what limits their potential as a full-fledged search tool. There are some things we are past consensus on, like the score of the Liverpool - Manchester United soccer game on September 1st, 2024. It might've been useful to see the odds in advance of the game, but now that it's over, it's more of an interesting data point about the divergence of what we all thought was going to happen versus what actually happened. That's one useful contextual point, but you would need to supplement it with more layers of context to fully understand the result of the game.

So, although their use cases might be limited to understanding things that have yet to come to pass, and they don't provide a lot of extra information beyond percentages, if someone like Komporozos-Athanasiou is right, and we have increasingly assumed the roles of speculators in our everyday lives, it seems natural to extend that attitude towards the way we search, as well. For my own part, I'd be interested in seeing what a non-commodified prediction market would look like -- translating the confederated wiki model to the interface of percentages and "yes and no" answers. We might see more interesting examples of contextual debates on topics that aren't immediately made to be turned a profit upon (like crypto, again...). But without money on the line, it would be a test of our incentives to get things right just to be right. Which I suspect, from a pride perspective, is also quite high.

Social Media (but really TikTok)

In 2022 a fair-minded New York Times article was published, titled "For Gen-Z, TikTok is the New Search Engine." The title, as they always are, is a bit hyperbolic, especially given that it hits on all the buzzwords that make corporate VPs lose sleep: Gen-Z! TikTok! Search Engine!

But it calls out a few behavioral shifts that are important to consider given the evolving nature of how and why people seek out information online. The first is the transition to more multi-modal responses to a query. Part of what attracts Gen-Z, according to the article, is that a 60-second explainer video about a recipe or how to ask teachers for a college recommendation is more helpful than a list of links that return mountains of text.

The other is that, despite the algorithmic sorting that TikTok uses, the fact that TikTok results return real people talking into the camera makes its results feel more authentic. This is a person giving their unfiltered, honest thoughts on a topic, not some "faceless website." That there isn't always a clear demarcation of what is ad-sponsored and what is not on, also makes the results seem "less biased," with the added benefit of having a comments section to either boost the veracity of the video's claims, or tear them down if it feels fishy.

Multi-modal results, real people, less perceived bias, and a comments section that crowd-checks a video's claims. This would seem to be a potent mix to challenge traditional search giants. But TikTok hasn't eaten into Google's marketshare at all. In the years since the article's publication, Google has only strengthened its position in the world of search.

This isn't to say that search marketplaces haven't been challenged by TikTok. Google has recently started to incorporate images and videos into its search results (they do own Youtube, after all). But TikTok has a misinformation problem. Because its algorithm is likely to keep you seeing stuff you're already pre-disposed to agreeing with, and because the dark side of "real people giving authentic opinions" is that those opinions could be wildly wrong, TikTok has struggled to moderate misleading content about all sorts of things like abortion, the war in Ukraine, and, of course, elections. TikTok is not in anyway immune to the omnipresent threat of getting radicalized by weird ideas that have plagued social media sites from the beginning, and it doesn't help that the app is designed to keep you on the app. At no point is it in a social media site's interest for you to look elsewhere for information, even if it's the responsible thing to do.

This is actually part of the reason why understanding that the value a search platform like Google provides isn't the answer, but the contextual overlay that provides the infrastructure of the answer. TikTok might, like the early instantiations of the LLM Answer Machine, provide a lot of answers, but those answers are either emerging out of an algorithmic blackbox, or coming from a person who could be totally wrong. It's telling that one Gen-Zer in the NYT article talked about using Google to fact-check things she found on TikTok. As I've said before, answers are cheap. Context and sense-making arcs are what matter.

The problem with the continual insistence that TikTok and other social media sites are replacing traditional search engines is that it paints an incomplete picture of what a search engine does. It's like saying your rice cooker is replacing your dutch oven because it cooks rice better, without considering that the value of a dutch oven extends beyond it's rice cooking ability (I'm aware you can cook other things in a rice cooker, but bear with me). Sure, TikTok might provide a more engaging retrieval experience, but after that you are swimming in uncharted waters with little in the way of understanding where these answers are coming from. The comments section goes some way in alleviating this problem, but it groups together people whose algorithms are all feeding them the same videos. It isn't actually a representative sample size. And even if it is, understanding where you fall on an issue in which people are disagreeing in the comments requires supplementary search tools so you can understand the context of the issue more fully. This goes some way towards explaining how TikTok actually drives more traffic to Google.

Some Final Thoughts

Traditional search platform marketplaces represented a foundational agreement upon which a lot of the free and open web was based: we scrape your sites for our index, in return, we send you traffic. Everyone wins. Except that, for the searcher, finding an answer to a very specific question can be taxing. The imperfection of the information you are dealt is both a benefit and a drawback of the traditional search experience.

That we now have technology that can summarize massive chunks of text into a single paragraph answer reduces that cognitive burden. But, in summarizing the answer instead of directing searchers to sites where the answer might live, LLMs have violated the tacit agreement of the free and open web. Here comes the lawsuits and the payouts, the agreements to pay sites to scrape their data for information. This will be interesting to watch unfold as the business model of search has now fundamentally changed. Will we see a world in which search engines become a subscription service? I shudder to think of a world in which search engines become like streaming sites: you need to subscribe to SearchGPT for access to The Atlantic and Google for Reddit and Bing for The New York Times (these are just representative examples, not real deals), in much the same way you need to subscribe to 6 different streaming services if you want to cover your bases, movies and TV-wise.

We should do our best to avoid this. But the lack of a different money-making consumer-facing use case for Generative AI seems to indicate that search is what these companies most believe in.

What I would say for the other two modalities and their increasing popularity is the following: search experiences are benefitted by crowd-sourced knowledge (as envisioned by Vannevar Bush's Memex, for those who read the first installment of this), the kinds of questions and answers being asked of search engines are changing -- they are becoming longer, multi-modal and users are increasingly suspicious of bias/being sold to when the alternative is a person they see as more authentic. Gone are the days of a short text question returning a solely text-based response. We have pictures and video now, and the ability to ask follow-up questions. These are now table stakes for search.

I am also in favor of exploring more ways we can codify collective social knowledge in ways that extend beyond betting paradigms. It's a sign of our post-2008 times that the prediction markets are an increasingly popular way we make sense of the world. But I'm eager to see a more expansive exploration of how we can pass on information to each other and build trust that extends beyond reviews and betting odds.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript