It’s a Wednesday night, and I’m on the phone with my mom when she hits me with: “Have you seen that KPop Demon Hunters movie”. Oh have I… I don’t tell her that I’ve listened to the soundtrack of 5 songs twice that day alone, once on my walk to work and once on my way home. My group chats are full of stickers of Rumi, the purple-haired lead, and other chibi versions of the movie’s cast. Two separate groups of friends are already planning Saja Boys costumes for Halloween. It’s one thing for me and my mid-twenties friends to be swept away by the latest trends, but why is my baby boomer mom, in her insular community of South Asian near-retirees in suburban Texas, asking me about KPop Demon Hunters?

Whether you’re already in on KPop Demon Hunters or not, you have undoubtedly experienced another part of the global phenomenon of Korean media. I remember “trying K-pop” in middle school. After Psy’s “Gangnam Style” blew the minds of the entire internet I decided to give the rest of the genre a try, but in 2012 there weren’t that many forums for K-pop that were socially viable to a middle schooler. Since then, Korean media has become more and more mainstream, with Parasite, Squid Game, and singer Lisa from girl group BLACKPINK on White Lotus just this year. Even without a streaming subscription, I’m betting you’ve heard BTS’ hit song Dynamite in your neighborhood Target more than once.

This mainstream global adoption (and often obsession) with Korean media is often dubbed the “Hallyu” wave. Hallyu has transformed South Korea into the cultural exporter that it is today.

Now, with our latest gem, Netflix has released the super mega hit KPop Demon Hunters: a Sony animated 1 hour and 36 minute movie about a demon hunting K-pop girl group called HUNTR/X (said “Huntrix”) sworn to protect humanity by using the power of friendship and music to maintain a magical barrier called the Honmoon, which keeps demons at bay. That is, until the demons decide to send in a sexy evil demon boy band to steal their fans and destroy the Honmoon! It’s all very positive and sterile and definitely made for your kids. The Honmoon is depicted as a golden shimmering veil that blankets the world, and represents the popularity of the protagonist HUNTR/X group. Their goal for most of the movie is to become so popular that the Honmoon is able to spread and cover the whole world to seal out the demons forever. Sounds familiar, yeah? The KPop Demon Hunters script was written and dubbed in English and has quickly become one of the most popular movies in the world. If the Hallyu wave was the Honmoon from the movie, there would be no chance of demons ever breaking through the veil.

Financial Origins:

This craze is a relatively new phenomenon, but not an untraceable one. In 1997 the Asian Financial Crisis deeply shook South East Asia and eventually crashed into South Korean markets. What started in Thailand, with the Baht collapsing under speculative pressure, rippled to Indonesia, Malaysia, and eventually to the uniquely and impressively sturdy South Korean economy. Post cold war and the US-overseen separation of North and South Korea, South Korea had forged itself a stable, albeit unconventional, pedestal to support their rapid industrialization. For decades, its growth had been astonishing: the so-called “Miracle on the Han River” transformed a war-torn country into a major industrial power within a single generation. But the miracle had a fragile foundation.

The chaebol conglomerates, the same family-run giants that gave us Hyundai and Samsung, were running on enormous debt and cozy ties to the government. As corruption and poor investments were brought to light, foreign investors fled, currencies tanked, and suddenly the floor gave way. By the end of 1997, South Korea’s foreign reserves were nearly gone, and the country turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for what was then their largest bailout in history: a whopping $58 billion USD.

The effects of that deal are still debated today. On one hand, the IMF loan prevented outright collapse. On the other, its strict conditions and governmental oversight hit ordinary Koreans hard. Under the terms of the loan, much of government spending was cut, companies were forced to shed workers, and the old guarantee of lifetime employment was dismantled almost overnight. Unemployment spiked, bankruptcies soared, and what Koreans began to call “IMF households” emerged: families suddenly living with uncertainty and precarity.

Where once stability meant a lifelong post at a chaebol, the new reality forced workers into a cycle of temporary work and continual re-training, shifting from industry to industry. The crisis was searing enough that many people still talk about it as the nation’s most painful event since the Korean War.

But yet, out of that rupture, new strategies emerged. In 1998 Kim Dae-jung was the first opposition candidate to win the presidency. He was a ripe 74 years old, making him the oldest president in Korean history. But his age did not stand in the way of his understanding of the value of pop culture. As one oft-repeated anecdote has it, the idea for cultural investment struck when Kim was informed that Jurassic Park had earned the equivalent of 1.5 million Hyundai cars in exports. A pretty damning realization for the president of an entire country to make! It’s easy to imagine his next train of thought: if heavy industry was vulnerable, why not invest in content– television dramas, films, music– as an engine for exports and influence?

Prior to the IMF, Korea’s cultural output had been tightly policed. Political dissent was cut from scripts and social critique was muted. That changed in 1996, when the Constitutional Court struck down key provisions of the censorship regime. When Kim Dae-jung took office two years later, he leaned into this liberalization hard.

As a democracy activist for much of his life, he saw the loosening of controls not just as a political necessity, but as an opportunity. Liberalization of expression at home could dovetail with economic liberalization abroad. And by giving filmmakers, musicians, and TV producers both room to speak, and resources to compete, Kim’s government effectively redefined culture as infrastructure: something to be built, funded, and exported.

K-pop Takes the Stage!

Initially differentiated as Korean music with a Western twist, it borrowed from hip-hop, R&B, and pop music and dance styles rooted in Black culture from America. In the 1990s, groups like Seo Taiji and Boys shocked audiences by rapping in Korean over New Jack Swing beats, sampling American fashion, and breakdancing on national television. For young people, it felt modern and rebellious. For their parents it was barely even music, let alone Korean music! Critiques echoed across newspapers and living rooms… which of course was the surest sign that K-pop was meant to take off.

What makes K-pop so powerful today is less about any single song and more about the system built around the groups themselves. Performers are called idols. K-pop idols are almost always products of a cutthroat and extensive trainee system. And they don’t just sing! Young hopefuls, sometimes as early as 12 or 13 are recruited by entertainment conglomerates and put through years of rigorous training: learning singing, rapping, dancing, foreign languages, media handling, and even etiquette.

However only a fraction of trainees ever debut in a group, and for those who are lucky enough to get signed, the grind doesn’t stop there. K-pop groups are designed as full-spectrum media engines. Often it is a constant campaign of TV and variety appearances, behind-the-scenes footage, livestreams, physical albums packaged with photo cards, fan-sign events, and a steady drip of social media posts. The idea is to keep your fans supplied with something to watch, collect, or interact with at all times.

KPop Demon Hunters makes this dynamic obvious. HUNTR/X is growing their fanbase through more than just releasing albums. They’re also plastered on ramen packaging, starring in variety shows, hosting meet-and-greets, and live in a massive glassy skyscraper with their logo on the top of it. The bit is that their hopes of sealing out demons depend on being seen everywhere. The IRL K-pop boy group BTS is an obvious real world parallel of a constant media generating engine.

Then there’s everything fans create themselves: TikTok dance choreo, fancams, fanart, cosplay, endless discussion threads, and themed cafes. The official machine and the unofficial community lovingly reinforce each other, until engagement doesn’t feel like a hobby you sign up for as much as just another piece of pop culture that takes up a corner of your brain. One day you wake up and realize that that corner has grown to a size healthy enough for you to get unreasonably excited when you hear a BLACKPINK song playing at your gym.

I recently spoke with a friend’s niece about her KPop Demon Hunters obsession. We talked about her favorite songs, which she sang for me, including unabashed attempts at the Korean bits. As a self proclaimed iPad kid, she regularly rewatches clips from the movie on YouTube. At 10 years old, she’s already living the logic of fandom: there’s always another video, another meme, another way in. But beyond just the movie, she has a much deeper exposure to Korean culture as a whole as I ever did at her age. This says a lot about how soundly South Korean media has woven itself into the lives of American kids in just over a decade.

Setting the blueprint

Back in my day, we had Japan. Everything was Pokemon and Naruto, Tamagotchi and Studio Ghibli. I grew up with a Gameboy Advance in one hand and Hello Kitty gel pens in the other, and I was getting into weekly smackdowns with my brother over Wii Sports. In Matt Alt’s book Pure Invention, he walks through how Japan has repeatedly captured the world stage through innovations in pop culture. The book has brought me to a fantastic realization that I think has more power than even Alt admits: teenage girls might be the most powerful cultural force in the world.

Sanrio, which not only sells plush dolls and plastic purses, but also $700 14K gold Hello Kitty rings, is the 8th largest licensor in the world, beating out Nintendo, Playboy, and the entirety of the NFL. Which I believe very much warrants a “girls rule, boys drool.”

In 1990, Japan was facing similar circumstances to 1997 South Korea. After nearly four decades of mounting financial glory and a new spot as the world’s second-largest economy, the Nikkei stock index began a sudden, steady decline. Japan didn’t get an IMF loan, and the depression lasted well into the 2000s.

Japanese companies still made world-class cars and electronics, but compared to their heady miracle years of the ’70s and ’80s, it felt like the music had stopped.

Enter: The Schoolgirls.

When the bubble burst, teenagers doubled down. Instead of buying the latest outfits and accessories, they made them. Everything from cosplay, to DIY manga, to new ways to wear your school-sanctioned socks in a way that looked dispassionately stylish. It was grassroots, simple and stitched together out of their allowance money and obsession. Even pagers got hacked into something new– teen girls invented emoticons to say what words couldn’t.

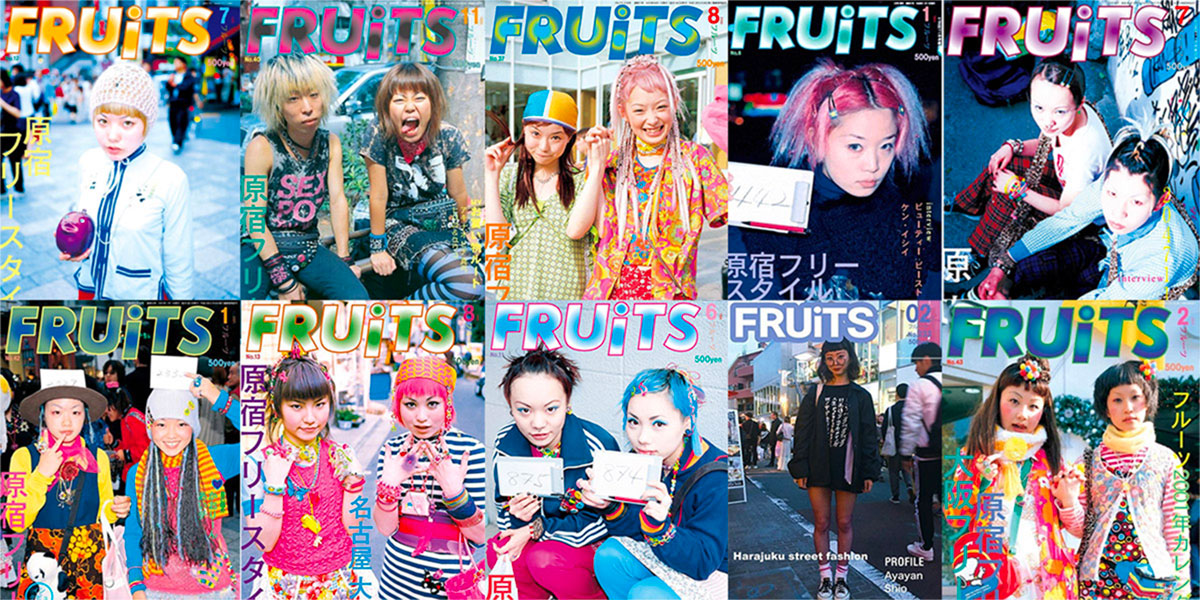

The Harajuku neighborhood in Tokyo was the teenage Mecca of the 90s. Kids would mob the bridge outside Meiji Shrine dressed in their twist on traditional Japanese clothing like kimonos, obi sashes, and geta sandals paired with thrifted finds and neon vinyl jackets. Nobody else on earth was dressing like this. Magazines like FRUiTS made the scene and Japanese fashions famous, and suddenly Harajuku took to the world stage.

Culture as Economy

The Korean and Japanese economic experiences are not one to one parallels, but there are crucial similarities. In Japan, economic dead-ends left teenagers building cultural empires out of keychains and cosplay. In Korea, the 1997 crash forced a wholesale rethink of what a nation could export.

When President Kim Dae-jung took office in 1998, he inherited an economy under IMF watch with millions out of work. In his mission to improve the economy through cultural diplomacy, he made a move that was cultural as much as it was political– ending a fifty-year ban on Japanese media. Suddenly, Korean households could legally watch Japanese films, listen to J-pop, and read manga. And just as importantly, Korean dramas and pop songs started flowing the other way into Japan’s vast and lucrative market.

The impact was immediate. At home, Korean producers had to raise their game to compete with the sudden flood of Japanese content. Abroad, they found audiences ready for Korean stories and idols, because Japanese youth culture had already made the world expect East Asia to be on the cutting edge. By the time K-dramas became a sensation in Japan in 2002, what people were calling the Korean Hallyu wave was seemingly more of a steadily rising tide– something state-backed, industry-driven, and global in ambition.

Sex and Evolution

In the clip of what is considered to be the first ever K-pop boy group, Seo Taiji & Boys, they perform their song “Come Back Home” live on stage in “snowboarder chic” outfits. This was never really done in Korea before, and for most Koreans it was scandalous or just another uninteresting fad. For teenage girls, it was everything they had been dreaming of: sexy, edgy, and American.

Seo Taji & Boys dancing in their snowboarder chic:

Girl groups, on the other hand, were initially built to be role models. While the boys were stomping around in baggy jeans and baseball caps, the girls were cast as their cherubic foils: demure, innocent, often styled as schoolgirls or guardian angels. Their songs leaned melodic instead of rap-heavy, their choreography was gentler, and the vibe was basically: here are some nice girls you can look up to, they are not scandalizing at all. But even in this “safe” packaging, the fingerprints of Western pop were everywhere. Outfits borrowed from American fashion catalogs, choruses were sprinkled with English words, and the overall effect was still unmistakably K-pop.

Girl groups being literal angels:

What’s interesting is that you can already see the blueprint for what K-pop would become. The “cute versus cool” binary was an easy shorthand that quickly disappeared as K-pop evolved, but both sides were borrowing liberally from the same source material- MTV.

As K-pop evolved into what we know today, the blueprint only got sharper. Groups stopped being just all “cute” or all “cool” and started operating more like ensembles, with a character for every type of fan. You’ve got the leader, the rapper, the dancer, the maknae (the youngest, who’s always a little sweeter). And within that framework, each idol was cast to hit a different audience fantasy. If you want the tough guy, he’s there. If you want the soft-spoken bookish one, he’s there, too. If you wanted the glamorous fashion queen, or the girl-next-door who feels like your best friend, done and done!

It’s also important to remember that this audience is overwhelmingly female, and the industry was built around giving them something to dream about. One moment that really blew the door open was Park Ji-yoon’s 2000 single “Coming of Age Ceremony”. Its sonically sleek early 2000s beat and breathy vocals were designed to feel illicit. Park blew that “girls are cute and innocent” mold up on national TV with lyrics that literally announced her shift into adulthood: “I’m no longer a girl… now I become a woman at your kiss.”

Kind of gross, but remember that the audience was full of young women also on the cusp of adulthood: this is something that they were already imagining. Why shouldn’t they have an idol who represented them? Rolling Stone later called it the era’s defining “sexiest” pivot. It was a lightning rod for pearl-clutchers and backlash. Which again, tends to be a big hit with the youths.

Park has admitted she had to live with the fallout for years, but doesn’t regret the controversy. It proved female idols didn’t have to stay in the “good girl” lane to succeed; they could claim desire and sexuality on their own terms. And who was paying the most attention? Young women. With boy groups, you picked your bias and imagined him as your boyfriend. With girl groups, you imagined yourself on stage, getting to dream what it might feel like to break out of your own box.

That thread only got stronger in the years that followed. By the late 2000s, groups like 2NE1 were bulldozing the concept of innocence. Their debut track “Fire” dropped in 2009 and it was an early example of a K-pop girl group that wasn’t playing coy. Instead they were stomping around in leather and neon, rapping, even snarling, and singing about self-confidence. The industry called it “girl crush,” but really it was just the next evolution of what Park Ji-yoon started: a way for young women to have idols who weren’t demure objects of affection but avatars of power.

Fast forward to today’s BLACKPINK and you can see the formula perfected. They’ve got the high fashion campaigns, the stadium tours, the trap beats, and a rapidly-growing global fandom. They’re undoubtedly tough and intimidating, but half the appeal is how pretty and fun and affectionate they are too. In July they released the absolute certified banger, “JUMP”. It’s fast-paced, energetic trot and euro-pop with big club beats and country western synths. The music video is bold-concept and playfully violent, but the lyrics are about sisterhood, freedom, and dancing with your friends.

A cool thing they do with “JUMP” is make fun of their own popularity. The video opens with zoom-ins on massive billboards with each member of BLACKPINK displayed, and then all four of them singing and dancing at the top of one. Below them are screaming fans who are thrashing and beating their heads into the walls in unison. It’s exaggerated and cartoonish, but that’s the point: they’re in on the joke. They know that the fandom is half of their story.

Back to the Demon Hunters

We have this same kind of nod of acknowledgement to the fandom portrayed in KPop Demon Hunters as well. HUNTR/X does the ramen ads, pops up on goofy variety shows, and hosts meet-and-greets where fans scream and cry and faint. The movie doesn’t shy away from the weirdest parts of fandom either– there are nods to shipping, fanfiction, and even jabs at the kind of fandom that snowballs into full-blown obsession.

So with all this momentum, how could you not be a fan? HUNTR/X basically checks every single box of the modern “girl crush” template. They’re confident, stylish, a little dangerous but still pretty and approachable, and the movie sells them as both aspirational and relatable to the girls sitting in the audience. It’s the same playbook groups like 2NE1 and BLACKPINK have run with for years: tough enough to stomp across a stage, soft enough to sing about friendship, and always locked arm-in-arm in a unified front of sisterhood.

What’s interesting is how KPop Demon Hunters bakes economic logic right into the plot. The girls in HUNTR/X are superheroes. While the world may not know it, HUNTR/X’s fame is literally a matter of national security– the Honmoon barrier only holds if they’re popular enough, and if it fails, the demons come pouring in. It’s silly, but it also rhymes with how K-pop has actually been treated in South Korea: they have spent the past two decades turning global fandom into a kind of national resource. Other countries dominate oil or tech, and yes, Korea’s top exports are still semiconductors and automobile production, but a lot of that success is due to global perception. Korea has turned cultural obsession into soft power, tourism, and billions in exports. The movie just makes that logic sparkly and literal.

Don’t worry, I haven't forgotten about the sexy demon boy band. In the movie, the antagonists take the form of a K-pop boy band called the Saja Boys, a demon idol group with neon hair, and cute outfits, hiding their demon markings underneath. They flirt, they smirk, they tactically take their shirts off, and suddenly whole stadiums of fans are switching allegiances. What’s funny is how spot-on this is with today’s real boy groups. They’re never just all “cool boys” anymore. More often, they’re deliberately quite androgynous: slender, styled, and svelte, leaning into softness as much as swagger.

With the Saja Boys, they’re caricatures of something that already feels a little cartoonish. The styling, the choreography, the way they talk to their fans is all real. That’s the whole point of K-pop: it’s synthesized and doesn’t pretend not to be. HUNTR/X and the Saja Boys may be animated, but they’re pulled from the same blueprints that actual entertainment companies have been sketching and refining for decades.

The entertainment conglomerate HYBE in particular has this blueprint of virality down to a science. They operate as a record label, talent agency, music production company, event management and concert production company, and music publishing house. It's bizarre but it's totally working, and for over ten years, they’ve been perfecting this machine of owning and operating K-pop groups. One of their most recognizable bands is BTS. They debuted in 2013 with their album 2 Cool 4 Skool as a scrappy, delinquent-adjacent, teenaged underdog crew, and then evolved in real time, into the biggest pop group on Earth. HYBE tracked how this model worked, and gambled on how to make it scale. Watching Saja Boys in KPop Demon Hunters, or HUNTR/X, you’re seeing the echoes of BTS’s approach: if you lean into the language of fandom, you get loyalty.

HYBE’s most recent viral success is KATSEYE. They're a six-member girl group with a multi-national lineup, singing almost exclusively in English and operating out of LA. To me, KATSEYE feels like the first proof of concept on the edge of a new generation of K-pop. HYBE is dipping their toes into what are now “global groups” and the K-pop template which once borrowed from the West is now being borrowed back, remixed, and released on Western soil with global labels.

So it’s worth remembering that as sparkly and fun as K-pop is, it’s still built on industry. After the economic crash of 1997 and the painful results of the IMF loan that followed, South Korea reinvented itself as a cultural exporter and patron state out of necessity. Hallyu wave emerged from President Kim Dae-jung’s gamble on using pop-culture as a tool for policy and diplomacy, all with the hopes of a bolstered economy in mind. Labels like HYBE are the legacy: infrastructure, global partnerships, content factories. The idols and the massive fan followings we see today are both the results and the mechanics of that expanding industry.

What was once Western was transformed by Korea, and borrowed by the West again. As this globalization advances, how much longer is “K-pop” even going to mean “Korean pop”? If the training happens in LA, the songs are in English, and the idols are global, what makes them Korean? Is it their dances? Their label? The fandom? These questions feel less and less theoretical with each debut. KATSEYE is doing all of this already, and HYBE just announced that they are developing a second global girl group to debut next year.

Much like the fictional golden barrier of the Honmoon, K-pop has undeniably blanketed the globe. If you’ve made it this far, I welcome you to the fandom: you probably understand more about it by now than most. Call it muddying of the waters or call it a melting pot (or the global-pop-industrial complex if you are funny like me), I’m just glad I’m tuned in to see what's next.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript