On the eve of the Paris Agreement’s 10-year anniversary, the math is sobering: to stay on a 1.5 °C pathway, the average person’s emissions budget in 2030 is roughly 2.3–2.5 t CO₂e per year which equates to about 6 kg a day. Contrast that with the United States, where the average citizen currently emits ≈14 t a year, or nearly 39 kg a day (GHG emissions of all world countries).

CO₂e is an imperfect metric—simplifying methane, nitrous oxide, and other gases into a single denominator—but it provides a relatable yardstick. The trouble is that kilos of CO₂e don’t feel as visceral as calories or dollars. Could design translate that abstract mass into an everyday reflex?

Tracking Your Planetary Calories

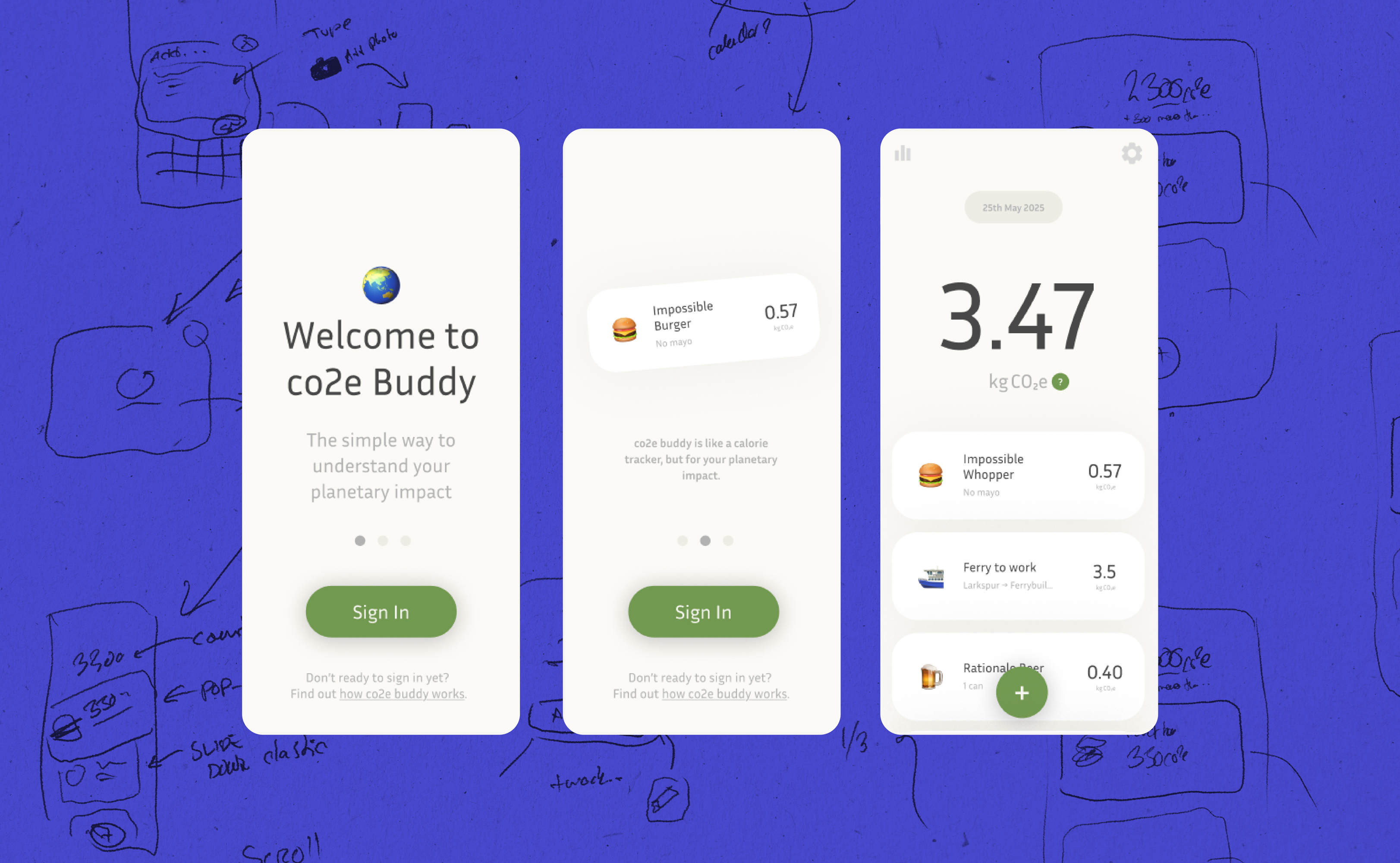

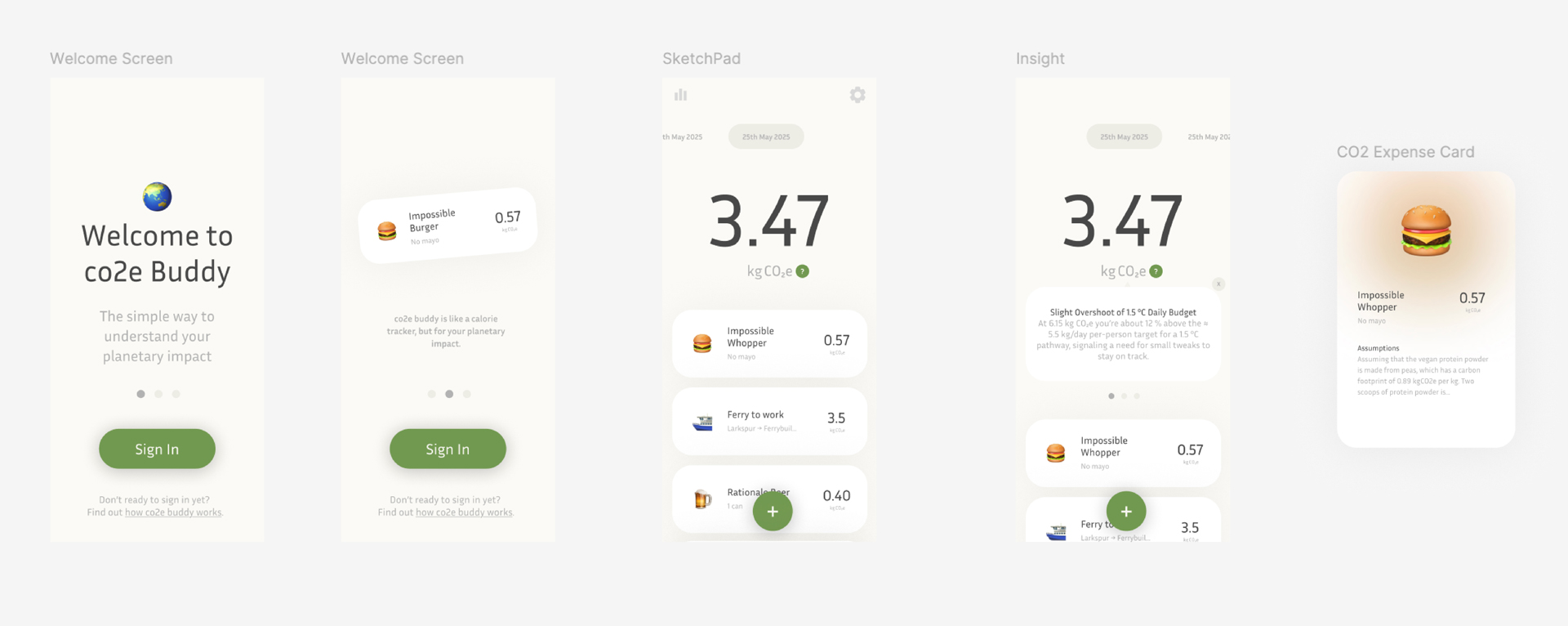

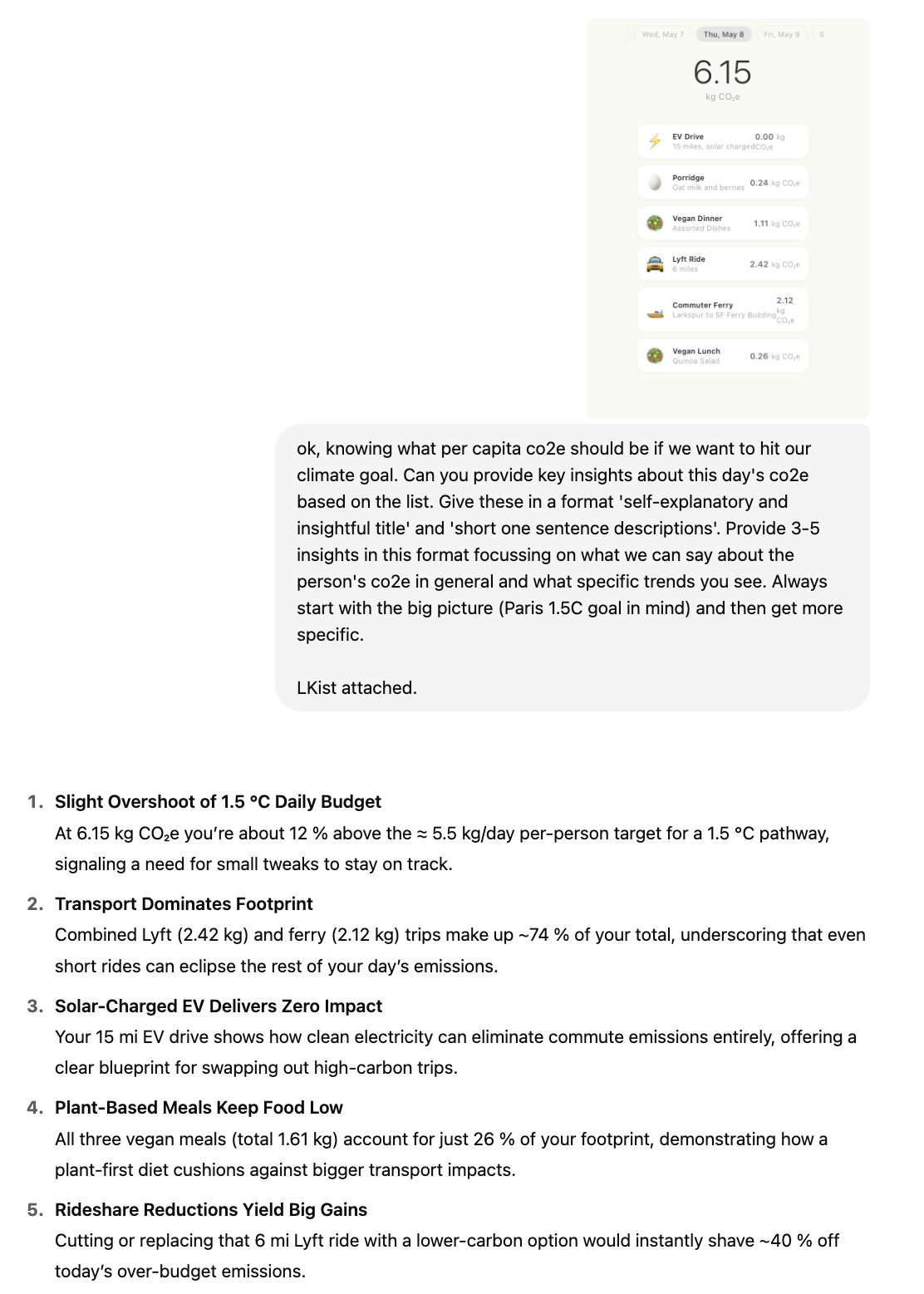

I wanted to help unpack this number by building a little tool. A climate ‘calorie’ tracker if you will. The same way food diary apps help people track their eating habits and in the process come to understand more about the impact of different foods on their health, I wanted to prototype an app that helps you understand your planetary ‘calories,’ and through this process perhaps learn something about the types and scale of change we as society need.

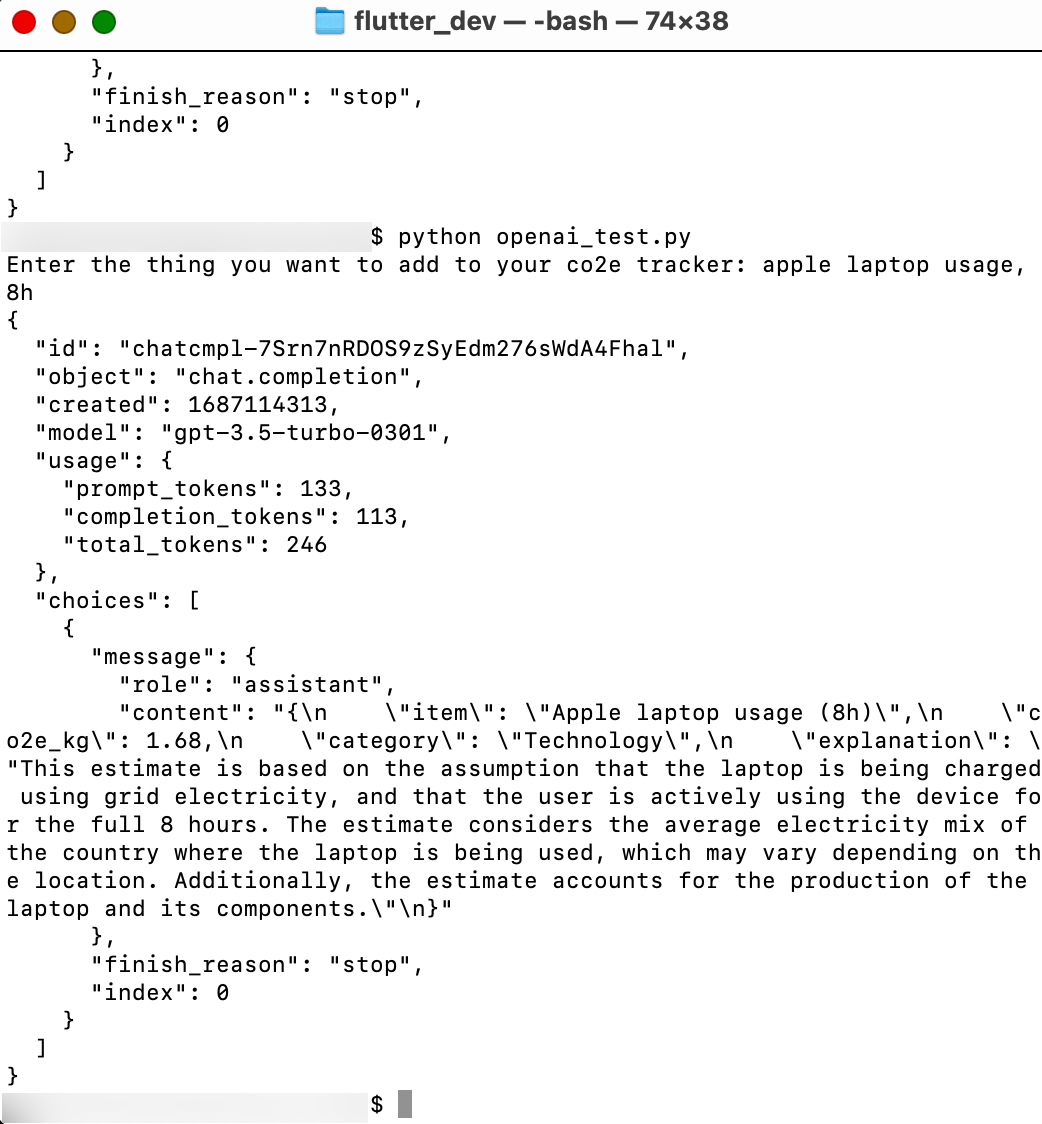

Users could simply type an activity like “commuting 20 miles driving”, “a vegan lunch” or “a flight to London from SFO” and the app would take that and give an estimate of the planetary impact expressed as a kg co2e.

This was an idea I had been thinking about for a bit of time, but never really got to fully building it beyond a very simple proof of concept written in python to test whether language models could actually give decent ballpark co2e estimates. However, about a month ago, the desire to experiment with AI enabled code editors (or IDEs) like Cursor made me return to this idea. What I was really wondering is: how quickly would AI pair-coding help me turn an idea into a functional, testable, intentionally designed thing?

Here’s how my day unfolded.

10am: Design it (very much without AI)

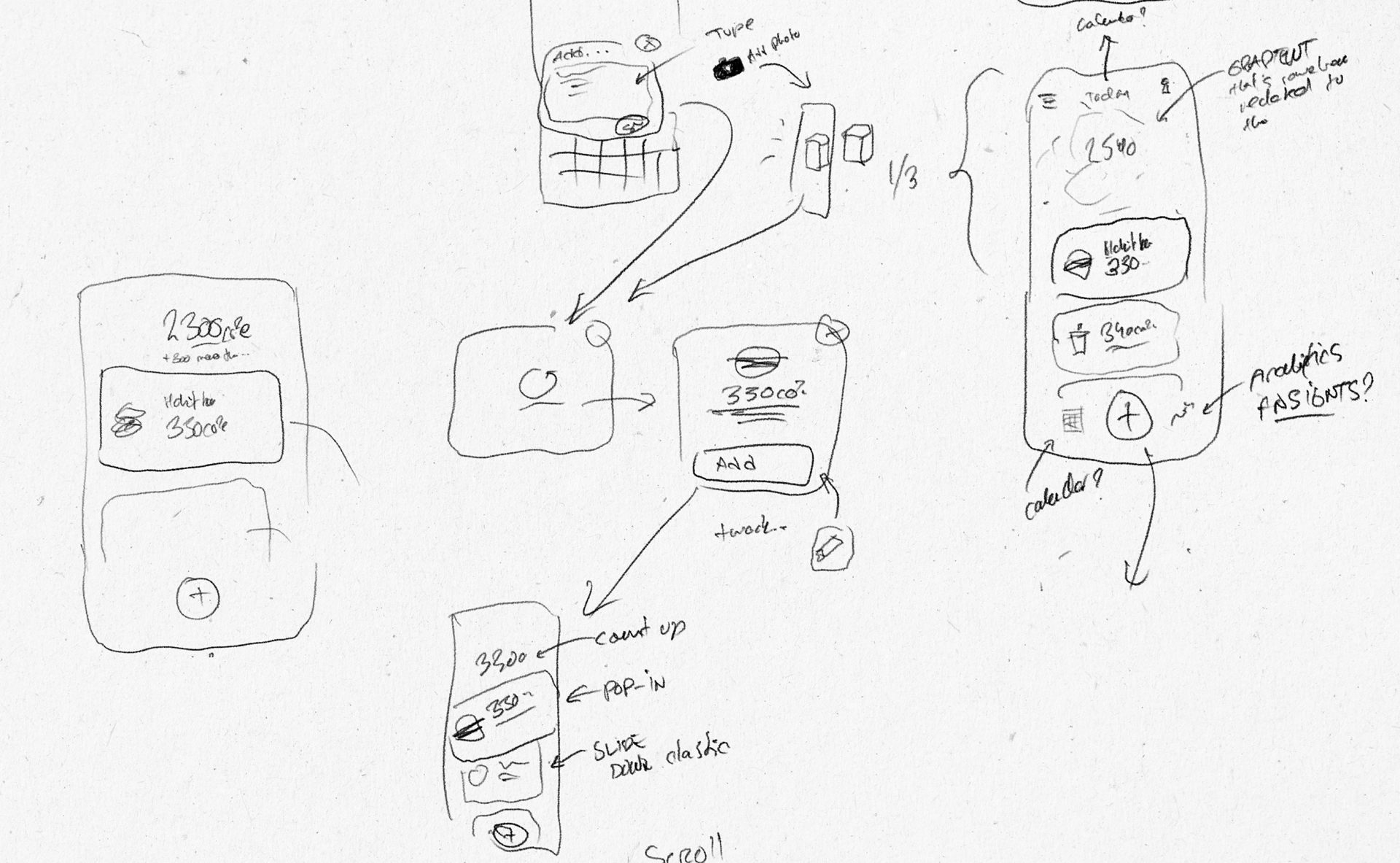

When designing a product, I like to start with rough sketches to figure out its signature, iconic moments, that translate the value the tool, product or service provides into a compelling and memorable experience. To me, the key here would be the daily co2e ‘calories,’ the ability to easily use natural language to add new activities for the app to estimate.

I quickly mocked up these doodles as a very simple product design with a focus on its key features: emphasizing the daily co2e number, a prominent ‘add’ button, a friendly list of activity ‘cards’ showing all the ‘activities’ as well as a minimal day navigation and a card for users to better understand how the AI ended up with the number it did.

11am: Pair programming with Cursor for the first time

I am a designer who codes, but is more excited about getting a thing up and running rather than getting deep into the weeds of the craft of coding. However, while tools like lovable or bolt are great for super rapid exploration, I still want to retain some sense of ownership over the code. This is why I was excited to start working with Cursor.

To start, I wrote a simple description of the intended functionality, specified the stack I wanted to use (React) and copy-pasted the main view while creating the basic scaffolding. After about an hour of prompting and tweaking the code, I had the basic front-end functionality of the app up and running with dummy data. A few prompts later I had the basic AI connection working too.

1pm: Hosting, database and user accounts

Once I had a ‘single player’ version up and running. I wanted to add hosting, a database to hold the content, and a basic user account. This is where Cursor really helped. Getting a simple prototype up and running has been relatively easy for a while now, but having an AI buddy to help you build the basic infrastructure to support it on its way towards production was a massive help. Cursor was my friendly AI engineer who was there to help with even the most basic questions when I got stuck, but letting me do the work and learn something in the process.

After asking Cursor for opinions and chatting through them, I decided to use Firebase for hosting, databases and user accounts. This was surprisingly straightforward - almost one-shot to get it working. In addition to helping with the code I found myself often dropping screenshots of Google’s admin interfaces (which could be way more user friendly, to be frank) to Cursor and having it walk me through places when I’d get stuck.

3-4pm: Just about done…

After finally noodling on small CSS fixes on padding, spacing and some other design details, I had my web-app up and running with a rudimentary onboarding flow, user account creation & management, AI co2 estimation, activity cards, navigation, and responsive design. The whole process took about six hours from never using Cursor to designing an app, making it functional and deploying it with (simple) infrastructure online. I was a fan.

Final Reflections

I have been a working designer for more than two decades now, fortunate enough to have seen and contributed to some of the major seismic shifts in how we think about interacting with technology. From pivoting towards streaming before Netflix even launched, to envisioning the kitchen of the future, what I’m seeing now is an approach to design that needs to borrow from and accelerate the HCD framework as we begin adopting AI tools to make, to learn, and to think of the new paradigms created by more accessible digital design tools. Sometimes, in a rush of excitement about a new suite of tools, it’s best to return to base principles first. How are we building on established frameworks to wade into new territory?

Some of the things I learned in my six hour sprint:

Supercharges prototyping. A lot of the work we do at IDEO is about making early ideas real so they can be experienced. This is the exact phase I see AI-coding accelerating. Chatting with my ‘real’ developer buddies, I hear the same thing: Anecdotally, in early stages AI-coding makes them 30-50% faster, but once you have a large complex codebase the speed addition is more in the 10-20% range.

Makes coding more accessible for designers. As a designer who codes (I am not a developer), tools like Cursor fit my workflow really well: I get to choose the level of help I want, choose where to take over or lean back. I also have a greater sense of ownership (as compared to browser based tools running on cloud) as I am running the apps on my local machine, installing libraries & modules and choosing when to deploy, push to github, and so on.

Use AI as a learning companion, not just a code generator. The temptation to just type “do it better” or something similar is always present, especially as models evolve to recognize what “doing it better” means. But that means you miss a valuable opportunity to actually plumb the depths of the tool you’re creating. Ask questions about why it made certain coding decisions. Ask about the feasibility of alternative flows. If you’re just beginning, ask what a callback function is or what a curl command does! The best way to learn is by doing, and the more you understand what you’re asking for, the easier it will be to actually duet with the code generator.

Prompting matters. If you’ve experimented with Cursor at all, you know you can get stuck in a doom loop. It tells you it has solved a problem, but then you point out that it hasn’t. It says “You’re right, let me fix it,” tries to apply the same fix, and still no luck. It can become fixated on a so-called “solution” that doesn’t work. This is why knowing what to ask for, and the inputs you give the generator matter. If you’re experienced enough to poke around in your code, you might be able to diagnose the issue that Cursor doesn’t see. Maybe it’s trying to pull from the wrong data source and the fix lies elsewhere. It also helps to take screenshots – showing your console running and the errors it runs into. The more context and specificity you can provide the code generator, the less it is left to its own devices. As a side note: one helpful trick is to make sure that you try and prompt your code generator to keep its fixes “concise.” Some models, especially Sonnet-4, like to take a lot of creative freedom and can build too much, which adds complexity later on.

Tap into github & version control to reduce the experimentation anxiety. Always connect your project to your Github account which lets you push to different branches (versions) of your project. This, in effect, saves your progress at the time you push your code to Github. You can always go back and restore that version so if you happen upon a situation where you need to backtrack: no problem. You can revert to the version before you made something that made Cursor angry.

Complex things are still complex. An app will not solve climate change. There is an entire network of systematic any and large influential governing or corporate entities that shapes what decisions we have available to us as consumers and as citizens. But even at a micro, app-level scale, there are still complexities to deal with. How will people respond to failing to hit their C02 emission goals? Will they double down or give up? What is the right incentive structure to keep people motivated for a healthier planet? How would the app need to communicate with you to be effective? What about how it scales? Would people be willing to share their data and possibly create network effects?

The point is that these are still deeply embedded human questions that are ensnared in large systems we often have a difficult time understanding. But what we can do is start to prototype the interventions that give us that agency back. That help us understand our choices, and begin to design for the behavioral changes we need, while continuing to advocate for similar changes at a systemic level.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript